"Charity Covereth A Multitude of Sins"

Part Two

by Thomas A. Droleskey

Our first pope, Saint Peter, the rock upon whom Our Blessed Lord and Saviour Jesus founded His one true Church, the Catholic Church, wrote the following in his first epistle, which can be seen as the first papal encyclical letter:

[1] Christ therefore having suffered in the flesh, be you also armed with

the same thought: for he that hath suffered in the flesh, hath ceased

from sins: [2] That now he may live the rest of his time in the flesh, not after the desires of men, but according to the will of God. [3] For the time past is sufficient to have fulfilled the will of the

Gentiles, for them who have walked in riotousness, lusts, excess of

wine, revellings, banquetings, and unlawful worshipping of idols. [4] Wherein they think it strange, that you run not with them into the same confusion of riotousness, speaking evil of you. [5] Who shall render account to him, who is ready to judge the living and the dead.

[6] For, for this cause was the gospel preached also to the dead: that they

might be judged indeed according to men, in the flesh; but may live

according to God, in the Spirit. [7] But the end of all is at hand. Be prudent therefore, and watch in prayers. [8] But before all things have a constant mutual charity among yourselves: for charity covereth a multitude of sins. [9] Using hospitality one towards another, without murmuring, [10] As every man hath received grace, ministering the same one to another: as good stewards of the manifold grace of God. (1 Peter 4: 1-10.)

Saint Vincent de Paul, the founder of the Congregation of the Mission and of the Daughters of Charity, was not a mystic. He was given no special private revelations from Heaven during his arduous labors in serving the poor as he would have served Our Blessed Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ in the very Flesh.

No suffering was too great for him to bear to serve the poor, whose presence he, chosen against his will to be a councillor at the court after the King Louis XIII of France, whose confession he heard before his death on May 14, 1643, preferred to all others on the face of the earth. It was one of the most severe penances of Saint Vincent de Paul's life filled with penances and mortifications and sufferings, including cruel service in slavery in what is now Tunis, Tunisia, in 1605 for a period of two years just five years after his ordination to the priesthood in 1600. Indeed, Saint Vincent de Paul had to match wits with the detestable Machiavellian, Jules Cardinal Mazarin, while serving as a councillor to the court of King Louis XIV during the time that his mother, Queen Anne of Austria, served as his regent until the child-king was old enough to govern between the years 1643 and 1651. Saint Vincent de Paul, thought nothing, however, of walking into the king's court in his old cassock, caring only that his garment was clean and had not been torn.

Ever self-effacing, thinking himself of little account and caring for not one blessed moment what anybody thought about him or his "reputation," Saint Vincent de Paul endured a great many slights while at court, which he simply shrugged off and offered up, knowing that he was serving the King of Kings Himself, Who was castigated and spat upon and mocked and vilified during His Passion and Death:

WHEN Louis XIII was on his deathbed, with all the Bishops and

Archbishops of France ready to offer him their services, it was M.

Vincent, the humble Mission Priest, who prepared him to meet his God.

During the last days of the King's life, Vincent never left him, and

in his arms Louis XIII breathed his last. Then, having done the work

for which he had come, Vincent slipped quietly out of the palace to

hasten back to St. Lazare and his beloved poor.

Some remarks made by the King during his illness and certain other

words of Vincent's were remembered by the Queen, Anne of Austria, who

had been left Regent during the minority of her son. Richelieu was

dead, and Mazarin, his pupil, a crafty and unscrupulous Italian, had

succeeded him as chief Minister of State. His influence over the Queen

was growing daily, but it was not yet strong enough to override all

her scruples. She was a good-natured woman, quite ready to do right

when it was not too inconvenient, and it was clear to her that of late

years bishoprics and abbeys had been too often given to most unworthy

persons. In France the Crown was almost supreme in such matters; the

Queen therefore determined to appoint a "Council of Conscience"

consisting of five members, whose business it would be to help her

with advice as to ecclesiastical preferment.

Mazarin's astonishment and disgust when he heard that Vincent de Paul

had been appointed one of the number were as great as Vincent's own

consternation. The responsibility and the difficulties which he would

have to face filled the humble Mission Priest with the desire to

escape such an honor at any price; he even applied to the Queen in

person to beg her to reconsider her decision.

But Anne was obdurate, and Vincent was forced to yield. "I have never

been more worthy of compassion or in greater need of prayers than

now," he wrote to one of his friends, and his forebodings were not

without cause. If Mazarin had been unable to prevent the Queen from

naming Vincent as one of the Council of Conscience, he had at least

succeeded in securing his own nomination. In the cause of honesty and

justice, and for the Church's welfare, the Superior of St. Lazare

would have to contend with the foremost statesman of the day, a

Minister who had built up his reputation by trading on the vices of

men who were less cunning than he. Well did Vincent know that he was

no match for such a diplomatist; but having once realized that the

duty must be undertaken, he determined that there should be no

flinching.

He went to Court in the old cassock in which he went about his daily

work, and which was probably the only one he had. "You are not going

to the palace in that cassock?" cried one of the Mission Priests in

consternation.

"Why not?" replied Vincent quietly; "it is neither stained nor torn."

The answer was noteworthy, for a scrupulous cleanliness was

characteristic of the man. As he passed through the long galleries of

the Louvre he caught sight of his homely face and figure in one of the

great mirrors that lined the walls. "A nice clodhopper you are!" he

said amiably to his own reflection, and passed on, smiling.

Among the magnificently attired courtiers his shabby appearance

created not a little merriment. "Admire the beautiful sash in which M.

Vincent comes to Court," said Mazarin one day to the Queen, laying

hold of the coarse woolen braid that did duty with poor country

priests for the handsome silken sash worn by the prelates who

frequented the palace. Vincent only smiled—these were not the things

that abashed him; he made no change in his attire.

At first it seemed as if his influence were to be paramount in the

Council. Nearly all the priests of Paris had passed through his hands

at the ordination retreats and those who belonged to the "Tuesday

Conferences" were intimately known to him. Who could be better fitted

to select those who were suitable for preferment? Mazarin, it is true,

objected to the Council on principle, but that was simply because he

considered that bishoprics and abbeys were useful things to keep in

reserve as bribes for his wavering adherents. Certain reforms on which

Vincent insisted were not to his mind either, although he offered no

opposition. It was not his way to act openly, and he bided his time;

the wonder was that Vincent was able to do what he did so thoroughly. (Mother F. A. Forbes, Saint Vincent de Paul, published originally in 1919 and republished by TAN Books and Publishers, pp. 65-68.)

"Monsieur Vincent," as our saint was called, cared not for human respect, explaining on many occasions that he was devoted to serving the poor as he would serve Our Lord Himself, expecting nothing other than contempt and ingratitude from those he assisted. That's right, Saint Vincent de Paul did expect, nor did he want, "thanks" for his efforts. He was merely discharging his duty, cognizant that the human condition is such that many recipients of generosity are not going to be grateful for his service to them. He was also quite grateful that he was mocked and reviled by those who considered themselves to be of "high station" in this world. He knew that the day of reckoning would come for all, that each person would have to make an account of his life at the moment of his Particular Judgment, that it was a great gift from Our Lord Himself to be able to suffer all manner of calumny for trying to be like unto Him no matter the lack of his "reputation" in the midst of the world.

Saint Vincent de Paul explained this as follows:

May God keep us from vain praise, flattery, and everything intended to attract the goodwill and protection of others. These are very low motives and far from the spirit of Jesus Christ, whose love ought to be the principal aim of all we do. Let these, then, be our maxims: To do much for the love of God, and not care at all for the esteem of men; to labor for their salvation, and not concern ourselves as to what they say of us. (Saint Vincent de Paul, as quoted in A Year With the Saints: A Virtue for Every Month of the Year, published originally in 1891 and republished by TAN Books and Publishers in 1983, p. 221.)

Let us be aware of complaints, resentments and evil-speaking against those who are ill-disposed to us, discontented with us, or hostile to our plans and arrangements, or who even persecute us with injuries, insults and calumnies. Rather let us go on treating them as cordially as at first, or more so, as far as possible showing them esteem, always speaking well of them, doing them good, serving them on occasion, even to the point of taking shame and disgrace upon ourselves, if necessary to save their honor. All this ought to be done, first, to overcome evil with good, according to the teaching of the Apostles; and secondly, because they are our allies rather than our adversaries, as they aid us to destroy self-love, which is our greatest foe; and since it is they who give us an opportunity to gain merit, they ought to be considered our dearest friends (Saint Vincent de Paul, as quoted in A Year With the Saints: A Virtue for Every Month of the Year, published originally in 1891 and republished by TAN Books and Publishers in 1983, p. 324.)

These quotations serve brutal reminders to those who prowl around the internet seeking who has "said what" about them to thank God if some injustice has been done to them by another.

Who cares if someone misunderstands us?

Who cares if someone has spoken ill of us?

Who cares if our true faults and failings and misdeeds are revealed to many before they are known to all men at the General Judgment of the living and the dead on the Last Day?

Isn't it good to suffer humiliation in this life as one seeks to make reparation for his sins and those of the whole world by offering up to God through the Sorrowful and Immaculate Heart of Mary whatever merit they earn for "earning their stripes" as soldiers in the Army of Christ? Is any one of us exempt from suffering as a result of our sins?

Is any one of us exempt from suffering to save the souls of others?

Why be so concerned about "protecting" one's "reputation," especially when so few people are even aware than any of us exists?

Our disordered self-love is such that we exaggerate our "importance" in the scheme of things, thinking that so many people are looking at what we say and what we do even though the reality is that we are nobodies who are invisible to all but a handful of people.

Saint Vincent de Paul's lifelong spirit of self-contempt was, if you think about it, a continuation of the work of a saint who was born thirteen years before himself, Saint Francis de Sales, another apostle of Charity and a foe of heresy, as is made clear in the book A Year With the Saints: A Virtue for Every Month, which, while quoting Saint Francis de Sales, comments on Saint Vincent de Paul's absolute disregard for what "others" would think of him for doing something that he knew to be right in the sight of God:

St. Vincent de Paul, too, was utterly opposed to worldly policy, and in his dealings with others was most careful to avoid all evasions and artifices. The very shadow of falsehood affrighted him, and he had a horror of equivocations, which deceive an inquirer by answers of double meaning.

7. When a simple soul is to act, it considers only what it is suitable to do or say and then immediately begins its action, without losing time in thinking what others will do or say about it. And after doing what seemed right, it dismisses the subject; or if, perhaps, any thought of what others may say or do should arise, it instantly cuts short such reflections, for it is has not other aim than to please God, and not creatures, except as the love of God requires it. Therefore, it cannot bear to be turned aside from its purpose of keeping close to god, and willing more and more of His love of itself. (Saint Francis de Sales, as quoted in A Year With the Saints: A Virtue for Every Month of the Year, published originally in 1891 and republished by TAN Books and Publishers in 1983, p. 208.)

Saint Vincent de Paul, apart from serving the poor without regard to what anyone, including the poor themselves, thought about him, was firm defender of the Holy Faith. He was almost solely responsible for the establishment of the seminary system in France that had been mandated by the Council of Trent in the Sixteenth Century. Only ten of the twenty seminaries that had been established in France at the end of the century in which Saint Vincent de Paul was born were still in existence in France by 1625. It was at the invitation of the bishops of France that Saint Vincent de Paul started giving ten day conferences/retreats to men who were to be ordained to the priesthood, gradually increasing the numbers of days into months and, finally, years, transforming what had been a haphazard, informal method of training men into the system that worked so very well under the infiltration of Modernism at the end of the Nineteenth and the beginning of the Twentieth Centuries. Saint Vincent de Paul was directing eleven seminaries at the time of his death at the age of eighty years on September 27, 1660.

Saint Vincent de Paul's zeal for educating future priests extended also to conducting yearly retreats for priests that were extended eventually to members of the laity. Over eight hundred people attended these retreats each year between 1633 and 1660. It is estimated that 20,000 people attended these retreats over the course of those twenty-seven years. His Congregation of Priests for the Mission, known today as the Congregation of the Mission, established universities in addition to seminaries, and although Saint John's University in Jamaica, Queens, was in the grip of the conciliar revolution when I studied there between February of 1970 and December of 1972 (completing the four year program in three years by taking summer session courses, something that prepared me to teach such courses just a few years later), there were a lot of older Vincentians on the campus who gave exemplary witness to Catholic truth, including several I knew from my ten years of on and off adjunct teaching (being paid per course) there between 1982 and 1992. I owe those priests quite a lot.

Saint Vincent de Paul's defense of the Holy Faith was as steadfast as his service to the poor. It was his love of Our Blessed Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ and of the souls for whom He shed every single drop of His Most Precious Blood on the wood of the Holy Cross that he opposed the coldness of the Jansenists who "baptized" the hardness of heart and the dark, dark spirit of the despicable heretic named John Calvin:

WHILE Vincent de Paul was striving, by charity and patience, to renew

all things in Christ, the Jansenists* were busy spreading their

dangerous doctrines. When the Abbé de St. Cyran, the apostle of

Jansenism in France, first came to Paris, Vincent, like many other

holy men, was taken in by the apparent piety and austerity of his

life. It was only when he knew him better, and when St. Cyran had

begun to impart to him some of his ideas on grace and the authority of

the Church, that Vincent realized on what dangerous ground he was

standing.

* So called from their founder, Cornelius Jansen, Bishop of Utrecht,

who died, however, before his heresy had been condemned.

"He said to me one day," wrote the Saint long afterwards to one of his

Mission Priests, "that it was God's intention to destroy the Church as

it is now, and that all who labor to uphold it are working against His

will; and when I told him that these were the statements made by

heretics such as Calvin, he replied that Calvin had not been

altogether in the wrong, but that he had not known how to make a good

defense."

After such a statement as that there could be no longer question of

friendship between Vincent and St. Cyran, although the latter, anxious

not to break with a man who was held in such universal esteem as

Vincent de Paul, tried to persuade him that he, St. Cyran, was really

in the right, justifying himself in the elusive language which was

more characteristic of the Jansenists than the frank declaration he

had just made.

Vincent, however, was too honest and straightforward, too loyal a son

of the Church, to be deceived. Realizing fully the danger of such

opinions, he soon became one of the most vigorous opponents of the

Jansenists, who, indeed, soon had cause to look upon Vincent as one of

the most powerful of their enemies. But although he hated the heresy

with all the strength of his upright soul, Vincent's charitable heart

went out in pity to those who were infected with its taint, and it was

with compassion rather than indignation that he would speak of St.

Cyran and his adherents. Not until they had been definitely condemned

by the Church did he cease his efforts to win them from their

errors—efforts which were received, for the most part, in a spirit of

vindictive bitterness.

The teaching of the Jansenists, like that of most other heretics, had

begun by being fairly plausible. The necessity of reform among the

clergy had come home to them forcibly, as it had to Vincent himself;

the Jansenists' lives were austere and mortified. The book which

contained their heretical doctrines, the Augustinus of Jansenius, was

read by only a few, and these mostly scholars. That the Sacraments

should be treated with the greatest respect and approached only by

those who were fit to approach them seemed at first sight a very

reverent and very proper maxim. Many people of holy lives took up this

teaching enthusiastically, among them some of Vincent's own Mission

Priests. When Antoine Arnauld, the youngest of the famous family which

did so much to further Jansenism, published his book Frequent

Communion, which might more truly have been called "_In_frequent

Communion," it was received with delight and eagerly read. That

Vincent clearly saw the danger is shown by one of his letters to a

member of the Jansenist company who had written protesting against the

attitude that St. Lazare was taking in the matter:

"Your last letter says that we have done wrong in going against public

opinion concerning the book Frequent Communion and the teaching of

Jansenius. It is true that there are only too many who misuse this

Divine Sacrament. I myself am the most guilty, and I beg you to pray

that God may pardon me . . . . You say also that as Jansenius read all

the works of St. Augustine ten times, and his treatises on grace

thirty times, the Mission Priests cannot safely question his opinions.

To which I reply that those who wish to establish new doctrines are

always learned and always study deeply the authors of which they make

use. But that does not prevent them from falling into error, and we

shall have no excuse for sharing in their opinions in defiance of the

censure of their doctrine."

The letter was answered by a second protest in favor of Arnauld's

book, which was met by Vincent with equal energy:

"It may be, as you say," he writes, "that certain people in France and

Italy have drawn benefit from the book; but for a hundred to whom it

has been useful in teaching more reverence in approaching the

Sacrament, ten thousand have been driven away . . . For my part, I

tell you that if I paid the same attention to M. Arnauld's book as you

do, I should give up both Mass and Communion from a sense of humility,

and I should be in terror of the Sacrament, regarding it, in the

spirit of the book, as a snare of Satan and as poison to the souls of

those who receive it under the usual conditions approved by the

Church. Moreover, if we confine ourselves only to what he says of the

perfect disposition without which one should not go to Communion, is

there anyone on earth who has such a high idea of his own virtue as to

think himself worthy? Such an opinion seems to be held by M. Arnauld

alone, who, having made the necessary conditions so difficult that St.

Paul himself might have feared to approach, does not hesitate to tell

us repeatedly that he says Mass daily."

It is evident that so cold and narrow a teaching could not but be

repugnant to a man of Vincent's breadth and charity. The monstrous

heresy held by the Jansenists that Christ did not die for all men, but

for the favored few alone, filled him with a burning indignation. No

one could have deplored more than he did the unworthy use of the

Sacraments; but he held firmly to the truth that they had been

instituted by a loving Saviour as man's greatest strength and as a

protection against temptation and sin. And he was not going to believe

that He who had been called the Friend of sinners and had eaten and

drunk in their company would exact from men as a condition of

approaching Him a perfection that they could never hope to attain

without Him.

Indeed, the chief aim of the company of Mission Priests was to draw

the people to the Sacraments as to the great source of grace, and it

seemed to Vincent that the means taken by the Jansenists to destroy

certain evils were very much more dangerous than the evils themselves.

It was better, according to his opinion, even at the risk of abuse, to

make the reconciliation of a sinner to his God too easy rather than

too hard. The rule of the Mission Priests lays down that "one of the

principal points of our Mission is to inspire others to receive the

Sacraments of Penance and of the Eucharist frequently and worthily."

The teaching of the Jansenists sought, on the contrary, to inspire

such awe of the Sacraments that neither priests nor people would dare

to approach them save at very rare intervals.

It was the great mass of the people—poor, simple and suffering, those

children of God whom Vincent loved and in whose service the whole of

his life had been spent—whose salvation was in danger. It was against

them that the Jansenists were shutting the doors of salvation. Is it

any wonder that Vincent de Paul fought against them as only men of

strong conviction can fight, with heart and soul aglow in the battle?

Compared with this all other evils were light. His business was to

relieve suffering, to comfort sorrow, but above all to help men to

save their souls. There could be no yielding, no compromise with

error.

Rightly, therefore, did the Jansenists see in Vincent de Paul the most

dangerous of their enemies, and it was not surprising that both during

his life and after his death they hated him and assailed him with

abuse. He was "insincere, treacherous, a coward," they declared. They

spoke of the "great betrayal"; they held him up to ridicule as an

ignorant peasant; but Vincent went quietly on his way. The question

"What will people say?" did not exist for him. He simply did his duty

as it was made clear to him by God and his own conscience. It was hard

to fight against such uncompromising honesty as his, and more than

once the man whose ignorance the Jansenists had ridiculed tore their

specious arguments to tatters with the weapon of his strong common

sense. (Mother F. A. Forbes, Saint Vincent de Paul, published originally in 1919 and republished by TAN Books and Publishers, pp. 74-80.)

It is so sad to see the spirit of Jansenism thrive today, not only in the counterfeit church of conciliarism, replete with is "liturgical reform" that is perfectly in accord with the Jansenist principles of the illegal Council of Pistoia that were condemned by Pope Pius VI in Auctorem Fidei, August 28, 1794, a condemnation cited by Pope Pius XII in Mediator Dei, November 20, 1947, but in fully traditional chapels where people are denied the Sacraments arbitrarily even though they defect from nothing contained in the Deposit of Faith and must sometimes live in fear of being expelled because of this or that dispute. Such a spirit of fear is that of Jansenism. The Sacraments are not weapons to be used to browbeat the faithful into accepting positions that have not been defined by Holy Mother Church or as a means to "punish" those who are critical of institutionalized abuses against souls. Saint Vincent de Paul fought against such a spirit. How sad to see its recrudescence both within the counterfeit church of conciliarism and in so many of our fully traditional venues.

As a defender of the Holy Faith, Saint Vincent de Paul urged Catholics to recognize that there can be nothing deception about the Catholic Faith, and that, contrary to the propositions of the naturalists, we must view everything about the Faith in lights of Its holy precepts:

We are firmly convinced that the truths of faith cannot deceive us, and yet we cannot bring ourselves to trust to them; nay, we are far more ready to trust in human reasonings and the deceitful appearance of the world. This, then, is the cause of our slight progress in virtue, and our small success in what concerns the glory of God.

Both for our own profit and the salvation of others, it is absolutely necessary to follow in everything the bright light of faith, which is accompanied by a certain unction secretly diffused in our hearts. Truly, there is nothing but eternal truth capable of filling our hearts and leading us in a safe path! Believe me, it is enough to be well established upon this divine foundation, to be sure of quickly reaching perfection, and being able to do great things. (Saint Vincent de Paul, as quoted in as quoted in A Year With the Saints: A Virtue for Every Month of the Year, published originally in 1891 and republished by TAN Books and Publishers in 1983, p. 281.)

And why are you still so interested in the blatherings of naturalists of the false opposite of the "right" who think that a return to "constitutional" principles will "save" our country when those very principles are premised upon the ability of man to "resolve" social problems and maintain a good social order without submitting to the Deposit of Faith in all that pertains to the good of souls and without a belief in, access to and reliance upon Sanctifying Grace? Nations founded on false, naturalistic premises (and Protestantism is NOT Christianity; it is hideous in the sight of God as it is a rejection and corruption of the truths contained in the Sacred Deposit of Faith) are bound to degenerate more and more over the course of time, something that will be explored once again in the article to be posted tomorrow, Friday, July 22, 2011, the Feast of Saint Mary Magdalen.

Recognizing that the work of his priests for the education of the clergy and the laity and in their service to the poor needed to be assisted by the prayers and charitable works of consecrated religious, Saint Vincent de Paul founded the Daughters of Charity, an institute that was so favored by the Mother of God at the dawning of the Age of Mary in 1830 as she appeared to Sister Catherine Laboure in the convent at Rue de Bac, giving us her Miraculous Medal of Grace through her (see In Ways That Baffle the Minds of "Modern" Men and In Ways That Baffle the Minds of "Modern" Men, part two), as she gave the Green Scapular to Sister Justine Bisqueyburo ten years later, that is, in 1840, knowing full well that we would need these sacramental aids as the wellsprings of Sanctifying and Actual Graces would dry up as a consequence of the very Jansenist-inspired liturgical "reforms" of conciliarism. This was Our Lady's way of ratifying the good work of Saint Vincent de Paul, who was so hated by the French revolutionaries that they sought to preserve his relics from the same fate of destruction that was visited those of Saint Louis IX, King of France.

How fitting it is that the heart of our saint, so filled with charity for the poor and zeal for the house of God, is still incorrupt, resting near the incorrupt body of his spiritual daughter, Saint Catherine Laboure:

Following many translations, his bones, which are encased in a wax figure, now rest in a magnificent reliquary in the chapel of the headquarters of the Vincentian Fathers, Rue de Sevres, in Paris. The head of the representation is said to be a true likeness of the Saint.

His still incorrupt heart, however, is enclosed in a golden reliquary which is exposed on the altar of his shrine in the chapel of the motherhouse of the Sisters of Charity, 140 rue de Bac, Paris. A short distance from this relic there is enshrined beneath a side altar the perfectly preserved body of his spiritual daughter, St. Catherine Laboure, the visionary of the Miraculous Medal. Also in this chapel on a side alter can be seen the the reliquary which contains the wax figure of St. Louise de Marillac, the co-foundress of the Sisters of Charity. The bones of the Saint are contained in the model.

It was often before the relic of Saint Vincent that Catherine Laboure, as a postulant and young religious, prayed for guidance from the humble priest who had favored her with a number of apparitions. (Joan Carroll Cruz, The Incorruptibles: A Study of the Incorruption of the Bodies of Various Catholic Saints and Beati, 1977, TAN Books and Publishers, p. 249.)

Saint Vincent de Paul worked hard in his labors for Christ the King until the very end of his life. God granted him length of days to do his work here on earth before he began his holy work for us from Heaven:

In spite of my age (79), I tell you

before God that I do not feel excused from the responsibility of working

for the salvation of the poor. For what could really get in the way of

my doing that now? If I cannot preach every day, all right, I'll preach

twice a week. If I cannot preach more important sermons, I will preach

less important ones. If the congregation cannot hear me at a distance,

what is to prevent me from speaking in an informal, more familiar way to

those poor just as I am speaking to you right now? What is to hinder me

from gathering them near me just as you are sitting around me now? - St

Vincent de Paul

Through it all, though, Saint Vincent de Paul, who cared only about serving Our Lord in the persons of the poor without regard to what others thought of his "madness" and poor appearance to the "self-important" even though they, like each one of us, would have to appear with their souls stripped naked of all pretensions and self-delusions at the moment of the Particular Judgment, relied tenderly upon Our Lady, especially by means of her Most Holy Rosary:

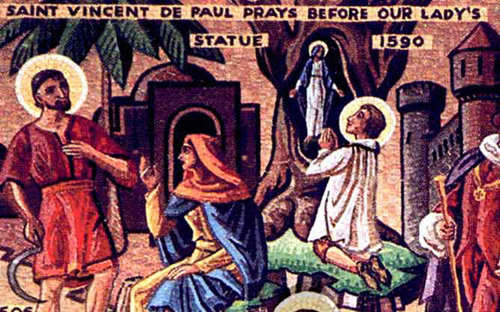

1590–Child Vincent prays to Mary.

In Vincent de Paul's youth there was no known

shrine to our Blessed Mother in the region of Puy, neither at Buglose

nor in a tree as pictured here. Nevertheless, he had for Mary a tender,

filial devotion and wished that this devotion be one of the most sacred

traditions of his sons and daughters.

Vincent wrote to his sons in 1656: "The

practice of wearing the Rosary on one's belt is always observed in this

house. I think it will be well for you to maintain in your house the

custom of wearing a rosary on the belt or to introduce it if it does not

already exist." In another place he declared, "It is a holy and

edifying custom." He told the Daughters of Charity: "The rosary is a

most efficacious prayer when it is said well. . . . It is your

breviary." (Mosaics of St. Vincent's Life.)

May each of whatever good works we perform as the instruments of Our Lady's graces in this passing, mortal vale of tears be rooted in the same filial devotion to Our Lady as Saint Vincent de Paul, a bridge, if you will, between the work of Saint Francis de Sales and Saint Louis Grignion de Montfort. May Saint Vincent de Paul help us to treat others as we would treat Our Lord and His Most Blessed Mother, counting it as our gain to die to self and to suffer for others to be more united with our Redeemer and our Co-Redemptrix, thanking God at all times for the occasions on which we are humiliated for doing good and calumniated for speaking the truth. We must remember that our sins deserve far, far worse than anything we can suffer in this life.

May it be the mercy of God upon our souls to help us to want to suffer more humiliation and misunderstanding so that we can plant a few seeds for the restoration of the Social Reign of Christ the King that was nearing its end in France by the time of the death of Saint Vincent de Paul.

Isn't it time to pray a Rosary now?

Our Lady of the Rosary, pray for us!

Vivat Christus Rex! Viva Cristo Rey!

Saint Joseph, pray for us.